Helen McCorry and Ian O. Morrison

The catechism project is intended to look at how information is sought and used in museums. There are many assumptions about how information should be organized in museum databases, most of them based on use of library databases, but very little in the way of surveys or research has been carried out.

Databases are relatively new in museums: many small museums and a surprising number of large ones still depend to a greater or lesser degree on manual systems. It is not always understood by staff why databases are built in the first place and management and staff often make sublimely different assumptions about how they should be used once available. External forces such as funding bodies sometimes exert pressure to help institutions realize the advantages of effective location control, but at the level of the individual curator these are often forgotten when the attractions of writing a really full description of a favourite object present themselves.

Because libraries also use databases to record and access information about their collections, and because libraries and museums are seen as similar types of institutions, educational establishments for the dissemination of culture, it is often assumed that the databases are used in the same ways and can be organized in the same ways. Of course, there are similarities: museum databases hold records which contain a large number of fields and can contain a high proportion of text; they contain descriptions which can be standardized; and they contain references to people and institutions which could be controlled by the use of authority lists. The differences, however, are significant. Libraries had cataloguing standards to which they worked for many years before the introduction of computers, in order to be able to exchange information accurately and quickly: museums have no such tradition of standards. Within a single institution, very different practices can exist side by side, justified by the requirements of different subject disciplines; different practices may exist within a department because new practices have been introduced without older records being brought up to date, or because the work of members of staff has never overlapped enough for them to consider doing things in the same way.

Another large difference lies in the difference between books and objects: while books are usually, although by no means always, similar examples of the same things - separate copies of the same book - museum curators when acquiring and cataloguing are usually concerned to identify that which makes the object distinct or unique. Coins are the only objects which are catalogued in a similar way to books and which, so to speak, have their names written upon them, but by and large descriptions of museum objects describe individual examples and depend on distinctions rather than similarities, even for natural history specimens where the uninitiated might expect one Lesser Spotted Pimplehead to be much like another. Where library cataloguing practices are adopted to record objects or even prints, much of the really interesting information ends up in an undifferentiated mass in the Notes, which cannot be efficiently searched because it is not broken down into separate fields.

When it comes to information retrieval, library subject access depends mostly on abstract concepts - facts, opinions, beliefs, arguments, theories, as well as some concrete things, while museum information retrieval depends mostly on the concrete - what, where, who, when. This distinction is far from absolute, but it does make it difficult to apply library classification schemes to museum collections.

While librarians have built catalogues so that they might know what they have and utilize it to its fullest extent, museums have been moved, one might say driven, to produce databases largely because of pressure from without rather than from within, from the National Audit Office, from donors who expect to be able to see something they had presented 40 years before, from rapidly expanding collections whose documentation could no longer be contained by a card file, and from a change in museum career patterns so that curators are no longer so likely to stay in one place amassing vast knowledge of a collection but will move on and expect to get to grips with new material within a much shorter time scale.

Lastly, while librarians have developed sophisticated search strategies in order to search vast databases at the other side of the world as accurately and cheaply as possible, museum searches still mostly take place inhouse and serendipity is more important than pinhead accuracy in supplying useful answers to `What material have we got which ...?' - providing good, thorough, accurate, up-to-date information inhouse is a higher priority than exchanging data across continents. Admittedly, the days of accessing museum information on international networks are already with us, and if one didn't know it before one need only use the Internet for five minutes to learn that the non-standardization of information raises barriers to retrieval, but this is an issue which affects more than just museum workers and will have to be addressed globally. Meanwhile, what can be searched and retrieved inhouse can probably be searched and retrieved internationally; if we get the first right the second is likely to follow, but if we devote our energies to arguing about the second the first will never happen at all.

These differences, combined with the absence of a tradition of using standards, means that the literature of library databases, about subject retrieval, authority files, search strategies and users' needs cannot be applied en bloc to museum databases. On examination, it transpires that very little work has been done on what sorts of questions are asked in museums, and much of what has been done has concentrated on `front-of-house' activities such as signposting and providing enough lavatories. At the NMS where we have been building both an internal database of the NMS collections, and a national database of collections in Scottish museums, we have often discussed these issues, concluding regularly that they are too often discussed without any reference to a body of knowledge, that assumptions are treated like established facts: too often untested assumptions are used as a justification for either doing nothing or for spending large amounts of resources on ill-conceived projects. We decided, therefore, to take a considered look at how information is sought in museums, and where appropriate, how databases go about answering them.

In the summer of 1993 we circulated staff in museums and galleries with a request for examples of the questions they are asked and the questions which they ask themselves. Of those who replied, many were very generous and we gathered a much larger total number of questions than we had anticipated.

Our intentions were twofold: first, to test our theory that the present approach to museum information is too highly structured and too theoretical and therefore discourages access instead of improving it and second, to learn more about what types of information are sought in museum environments, particularly types of information which can be stored on databases.

REPORT

We sent out 281 forms with a covering letter, and handed some out personally as well. The total number was about 300. We only contacted people we already knew: There was no mass circulation or cold calling. Our targets worked in a wide variety of museums, including national museums in London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast, large and small museums in Scotland and England, and a very few establishments abroad. We sent out the forms at the beginning of August, not setting a deadline at that stage, and then one month later sent out reminders (in the form of postcards of the NMS collections, often carefully matched to the recipient) giving a deadline at the end of September. We also sent out Thank You postcards to everyone who sent us a reply.

We have received over 100 responses, and although we only asked for five questions from each respondent, some people were kind enough to provide a very wide range of different types of enquiries, scouring their correspondence files to do so, and so we had a final total of 1013 questions to examine.

Although we had asked for genuine questions, some respondents sent examples of types of questions, such as `Do you have any paintings by a particular artist'. This defeated our purpose of testing reality rather than assumptions, but did give an idea of the most commonly asked questions. We used these in the first part of the survey, examining what type of questions are asked generally in museums, but excluded them from the second part where we looked at questions about museum objects.

We had hoped to receive a high proportion of questions which museum staff ask in the course of their work, but in fact there were very few examples of these and most were to do with procedures. According to the examples, curators and education staff almost never ask themselves questions about the objects: this is presumably not true and is a consequence of respondents assuming we were more interested in enquiries from outside. Future researchers should be more explicit about seeking to examine inhouse information.

We would like to thank our colleagues who obliged us with questions: some obviously enjoyed passing on favourites - Was Pontius Pilate really born in Perthshire? and When does the next boat leave? - and many were very thorough in ransacking their files to give us a wide range. The usefulness of the results is a direct consequence of their helpfulness.

First stage - Types of questions

First, we went through all the questions one by one, sorting them into categories. We included questions which one would not expect to be answered by a database, such as `Where is the Ladies?' and `Why can't I use flash in the gallery?', at this stage because we wanted to get an idea of what place the database, whether it exists on paper or in electronic form, holds in providing information, and what proportion of need it satisfies.

The categories were suggested by the questions themselves and were created on an ad hoc basis: as a result some of them are difficult to describe but they will be familiar to anyone who has answered questions in a museum.

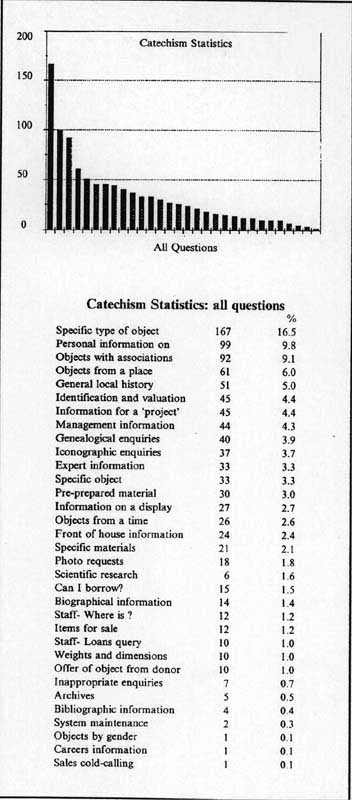

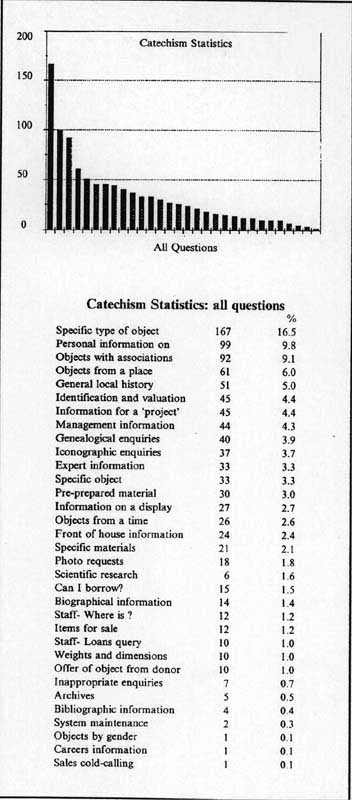

The results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Of these questions, 695 (69%) were subsequently used to test the databases. This shows that over two thirds of the questions asked are questions which might be answered by using a database or other catalogue, while the remaining one third are answered in other ways. These include looking up dictionaries of biography or local histories, checking files of similar information held in the museum, sending out pre-prepared information sheets, following policy, identifying objects, supplying front-of-house information, and simply providing the sort of information that one has in one's head after working with the same collection for a number of years.

Museums receive enquiries about topics which do not relate directly to their collections and many of them take the helpful line of supplying the information rather than re-directing the enquirer: there are probably for instance far more museums supplying information about dinosaurs than there are which hold significant amounts of dinosaur material. These enquiries vary from the unsophisticated `I am doing a school project on ... ', through the amateur genealogist or local historian wanting fairly specific information, to the researcher working on a book or PhD who is asking for permission to come and do research themselves (or, indeed, expects the curator to do it - and by the end of next week). Of our sample this type of question formed the bulk of the questions which would not usually require reference to the catalogue, database or, in other words, do not refer directly to the objects in the collection.

The commonest sort of enquiry accounts for rather more than 15% (167) of the questions and relates to a specific type of object. If requests for information about specific objects are added, the total is 19.8% or almost one fifth. The next most commonly asked question does not relate to the museum's objects directly but seeks associated information on a subject, an individual or an event. This does not include school projects, only the more serious sort of enquiry: if it is combined with information for projects it totals 14.2% (144). This is very close to being the commonest sort of enquiry and shows the high proportion of enquiries museums receive about topics other than their own collections. They differ widely in their practice on replying to such questions, according to resources as well as policy and staff attitudes.

The proportion of iconographic questions will vary enormously according to the nature of the museums's holdings. Art galleries might receive requests for Indian miniatures that depict the Churning of the Mighty Ocean: museums for all Greek and Roman antiquities which depict Hercules or musicians; and holders of large photograph collections receive endless enquiries for pictures of shopfronts, fishermen, people wearing spectacles, steamers passing the Isle of Arran, `people of colour', and pre-1930 motor cars. Requests for images vary from the impossibly vague, like the visitor who asks if the Imperial War Museum if they have any film of warfare, to the frighteningly specific `rivet-counter' who wants to know how many rivets were used in a Mk3 Avro Lancaster.

Identification and valuation of objects comes fairly high up the list, including requests to identify and value objects which are neither produced nor described - `I have an old yoyo. What is it worth?' - requiring the curator to have skills in telepathy as well as the more usual abilities.

The very low figure (0.4%) for bibliographical enquiries probably reflects the fact that a number of the responding museums have libraries to which relevant enquiries are passed rather than that people don't ask bibliographical questions in museums. As discussed above, information use in libraries is already the subject of considerable research and we did not attempt to repeat it here. We did not seek questions from museum libraries.

After enquiries about objects associated with a particular person, company or place, there are no clear leaders amongst types of question asked: a very wide range of headings have a very similar (low) number of responses. Enquiries cover a very wide range and engage staff in a very wide range of activities in order to answer them. In a large museum these activities are carried out by different departments so that the person who replies to a written enquiry about the provenance of a teapot will not be the one who says where the Ladies' is, or checks the location of a bald-headed eagle, but in a small museum there will be much more overlap.

Second Stage - Categories of information

Next, we looked at the questions which related to the objects and which would be answered by referring to object records such as a card catalogue or automated database.

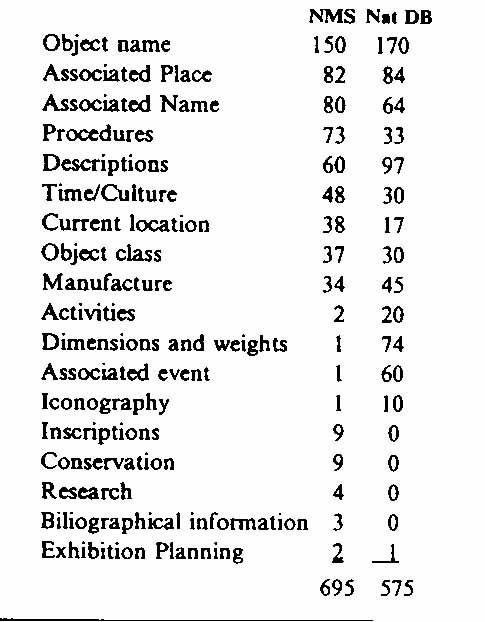

We categorized these by what they were about, in database terms what `field' of information they require one to search. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Object information

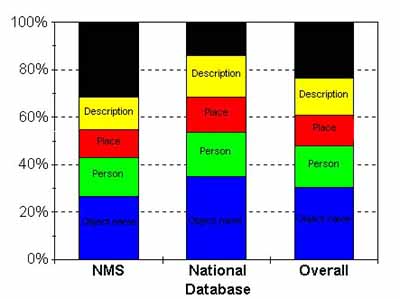

The number of enquiries relating to a specific object has the highest frequency, averaging 30%. In this case, "object name" has been combined with "object class". It is hardly a revelation to establish that if a museum is going to record only one thing about an object it should be a note of what it is. What is surprising perhaps is the lack of a clear runner up as to the next most useful thing to record.

Place names associated with the object such as place of origin or manufacture are almost as important as the names of makers, owners or institutions. If such associated information is combined it is used as often as "object name".

Descriptive information about objects, including references to iconography, inscriptions, dimensions, materials and media was used to answer 16% of the object-related queries. This information is often time-consuming to collate and enter, particularly if terminology controls and classification schemes are in operation.

Information relating to "procedures" involved in the acquisition or management of the object, including source name, date of acquisition, and current location loans, is also of importance, representing 13% of those queries sampled. This figure is possibly misleading as a result of respondents not supplying us with examples of inhouse questions and in reality, staff probably need to ask these questions more often than the sample shows.

All other categories of information, including date, period or culture of the object, associated events, research and bibliographical information were involved in answering less than 10% of enquiries.

The number of enquiries relating to iconography will vary a great deal according to the nature of the collections, being led by institutions which have major photograph collections, followed by those holding paintings.

The questions of what, where and who are the questions which computer databases can answer most easily, along with those about where an item is currently stored.

One of the present writers did a considerable amount of work a few years ago, trying to establish what constituted the `optimum minimum' amount of information one might want to record about a museum object in a database: the results were inconclusive and it is clear from the figures why this was. There are simply too many possible areas about which questions might be asked for a clear order of priorities to emerge. It is essential therefore that before one starts gathering information for a database, one knows why it is being built and what one hopes to do with it when complete, in order to concentrate the mind. Since accountability is usually a driving force behind such a decision, register number and location provide the simplest starting point: other areas must be considered and either selected or abandoned. Staff carrying out input can be very tempted to include everything but the kitchen sink, whether they are copy typists or senior curators: this temptation must be resisted and if necessary, thwarted.

People seldom ask a question which they do not expect to answer, so perhaps the reason that questions about weight and dimensions figure so low is because few institutions have been able to look up weights in their registers. If they know that they keep a record of weights of objects in a database, they are much more likely to look it up to check.

Similarly, perhaps the reason that so few people ask `Where is 1923.45?' is that registers have seldom been used to record locations, which are more likely to be sought in a shelf list - in location order or in a set of cards.

Conclusions

A majority of queries required more than one field to answer in full. Most queries required a free-text search within an appropriate field, but the search terms tended to be fairly specific.

The most important piece of information to record is what the object is, hardly a surprise, although the level at which this needs to be done varies and more than one level may need to be accommodated. Next, a long way after that, are place names. These may be where the object was made or found, or where it was used. Names, of makers, owners and others associations come next, so close that the difference is probably not significant. The names may be of individuals or organisations.

Questions about procedures follow. This is information to which one would give a high priority to recording anyway, for accountability reasons. Physical description of the object is not a major area of inquiry, although for some collections it may be vital: for all collections it will matter at some time or another. It is one of the hardest areas to control for retrieval purposes, curators often being reluctant to use a controlled vocabulary or a standard cataloguing style.

It should be remembered that these figures are drawn from a comparatively small sample, although a widely distributed one, and the fact that a percentage is low does not mean that it represents a total number of enquiries which an institution can afford to ignore.

This was a very general survey, done from a wide variety of sources. Individual museums and collections within museums will sometimes have different priorities. This should not be used as an excuse however for gathering information in an unplanned and poorly organized way, nor as an excuse for not gathering information at all.

[It is clear from this analysis that object name, or high-level classification, is the most useful piece of information from the point of view of retrieval. Associated people and places together account for about the same number of enquiries as object name. Descriptive information is of more use for answering external enquiries, and procedures for internal ones.] National museums, by their nature, attract more academic enquiries, with a wider range of areas of interest. Smaller museums tend to attract more enquiries of the type "My granny, x, gave you y in z, can I see it?", where x is a personís name, y is an object name and z is a date.

Since What, Where, Who and When come out ahead and that's what computers are good at, presumably the way ahead should be to look more closely at ways to standardize and simplify how we record these elements rather than worrying at this stage about the nuances of description.